Our lives are full of misunderstandings that we don’t even know are misunderstandings. We have identified misunderstandings and then the misunderstandings that we will never know existed.

If, after a conversation between two people, you separate them and ask them to recount the conversation, you will undoubtedly get two very different stories about the conversation. They will most of the time relate that things were said that actually were not spoken. And they will believe it. They will call it “my truth.” I don’t agree that it can or should be considered truth if your brain added the subtext. At that point, it is really more about a story you have made up in your own head and believed it. That is no more truth than is a daydream fantasy of winning a million dollars.

Subtext is at the root of so many of our misunderstandings. Subtext informs how you hear or interpret almost anything. By definition, subtext is underlying and implied.

Subtext (noun):

An underlying and often distinct theme in a piece of writing or conversation.

Oxford Languages

Subtext is made up of the words that your brain fills in when those words weren’t actually spoken. The subtext we choose to believe (however subconsciously) then changes our reality.

Furthermore, the subtext that our brains choose to fill in is heavily informed by the internal messages and beliefs we have adopted about ourselves, others and the world. We pass everything through the filter of these messages and they come out the other end looking different than they might have been intended.

Rather than continuing to allow subtext to alter the flow of our conversations, we should start training ourselves to make clarifying meaning the root of all communication.

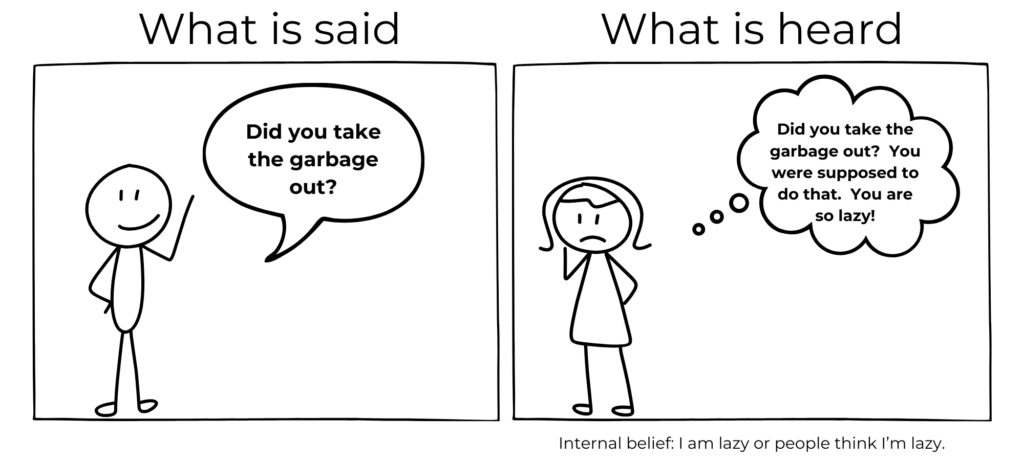

Imagine that your partner asks you the simple question, “Did you take the garbage out?”

If you have the internal belief that you are lazy or that people always think you are lazy, you will likely hear the subtext: “You are so lazy,” in which case you will react defensively to the simple question of “Did you take the garbage out?” because you will actually hear, whether in tone or even in imagined words, the message that you are lazy.

Similarly, if your partner asks if you took the garbage out and somewhere inside, you are afraid that you just might fail at everything you do. If that’s the case, you might hear the subtext (the underlying meaning) or you might even swear that you hear the words “You can’t do anything right.” When you were actually asked the simple question of “Did you take the garbage out?”

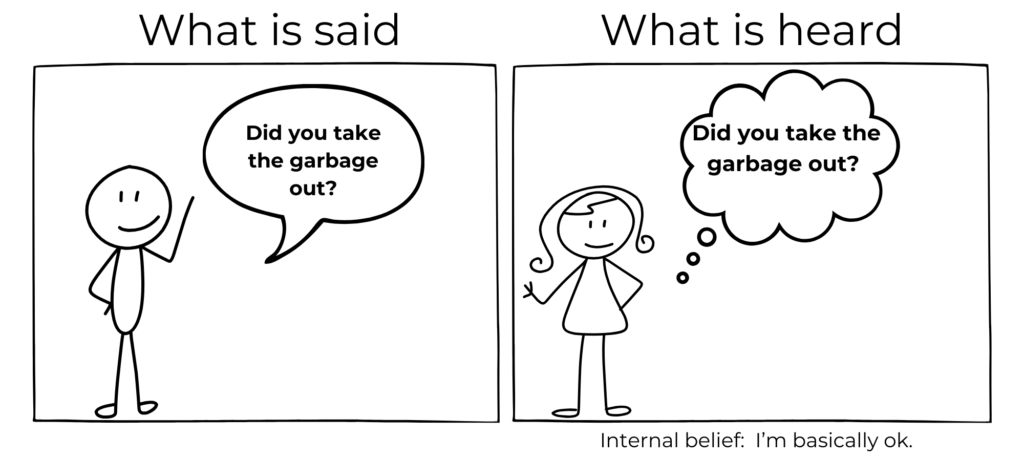

Imagine a world where we only hear the question asked. If your partner asks you if you took the garbage out, and you hear the question, “Did you take the garbage out?” It sounds simple and it really is, but it isn’t easy for some people. It is worth the effort, though.

How can you start substituting subtext with clarity? Well, the first step is to recognize when you are guilty of adding in words. That is not as easy as it sounds, though, because so many of us are doing it subconsciously. We really believe we hear the words that our brains are adding in. So, the first step is to catch yourself in the act of letting your mind fill in words or meaning.

Once you recognize that you are doing this, and we all do it at least sometimes, challenge yourself to slow down and listen to the words spoken. Even if you feel absolutely certain that you know the intended subtext because the person speaking to you is very familiar to you, assume that you do not know any meaning or intention beyond that which is spoken.

Then seek clarity, especially if you are able to discuss this new endeavor of yours with the person you are seeking clarity from. For example, it is certainly possible that your partner is indeed upset that you didn’t take out the trash. If you think you might sense this, it is absolutely ok to ask if that is the case. And if your partner is also attempting this exercise of not adding subtext to your messages, it is possible for the two of you to have an open, honest exchange.

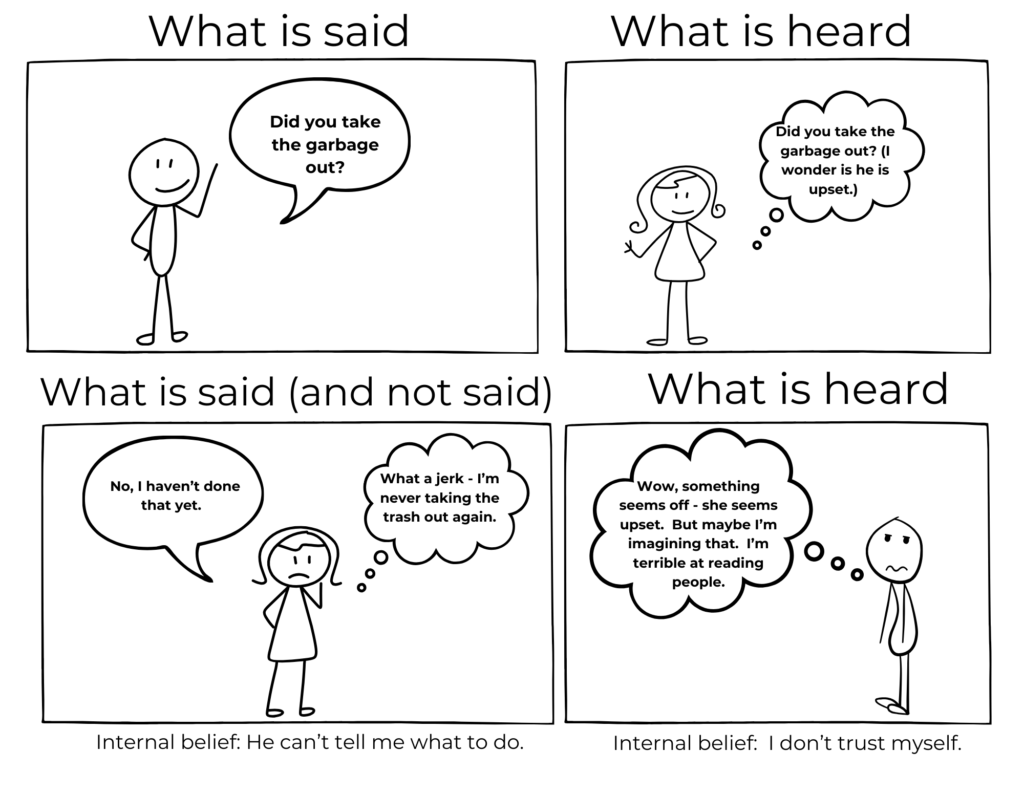

However, especially if the person you are talking with is not aware of all of the subtext and meaning being added to conversation, it is possible that when you ask the clarifying question, the question itself will be misinterpreted. Your partner might read meaning into your clarifying question or think that they actually hear words that have actually not been spoken. This is demonstrated in the cartoon below.

It is easy to see how this could spiral out of control. When neither person is aware of what they are adding to the words or the meaning in their heads, a misunderstanding can soon ensue.

Imagine another scenario where the person doesn’t ask for clarity – she just indulges her interpretation of the tone, or body language, or imagined subtext. Notice how it still spirals out of control and ends in not only a misunderstanding, but in a subversive (not identified or surfaced) misunderstanding. Because the misunderstanding isn’t identified, it’s not acknowledged or addressed, and further interactions will reflect the negative feelings from this brief interaction about trash. It doesn’t take long for the people involved to forget how the bad feelings started and just start treating each other poorly.

While this might feel like a complex problem to solve, it really all boils down to listening and stopping yourself from adding any words or meaning not stated by the other person.

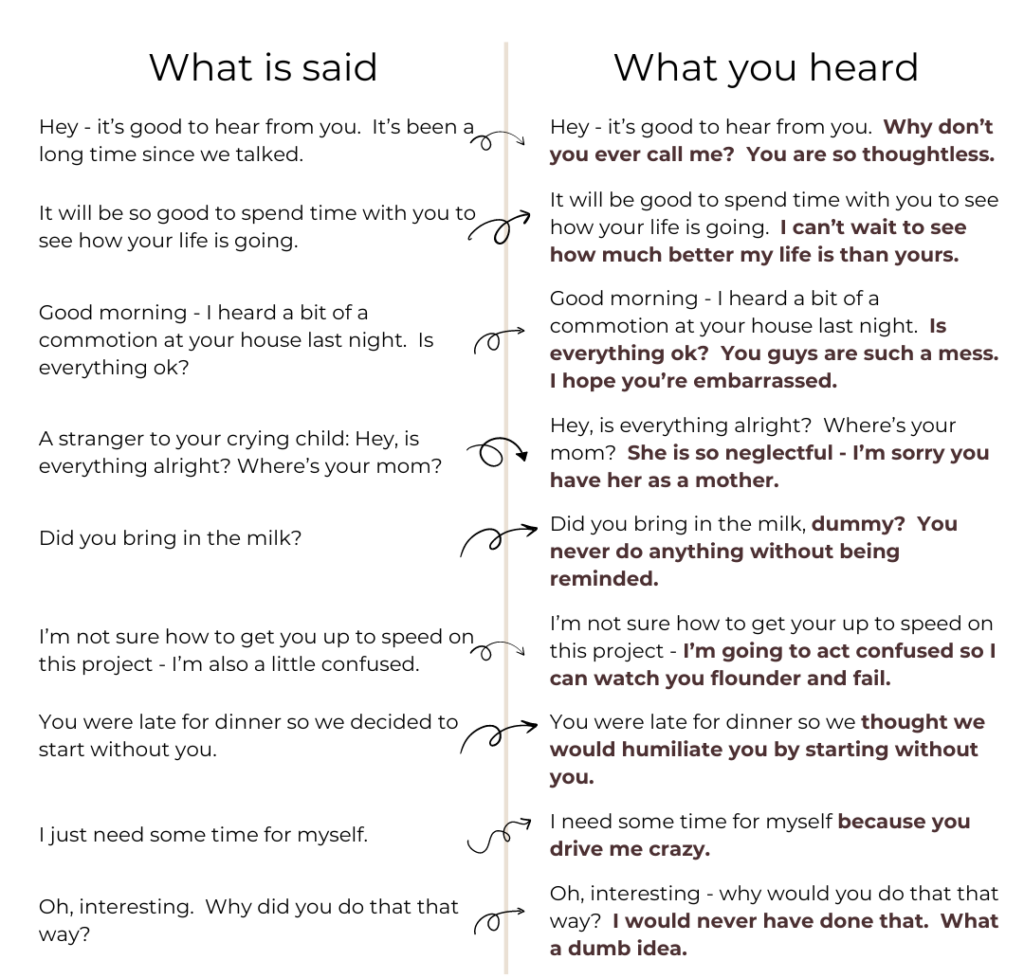

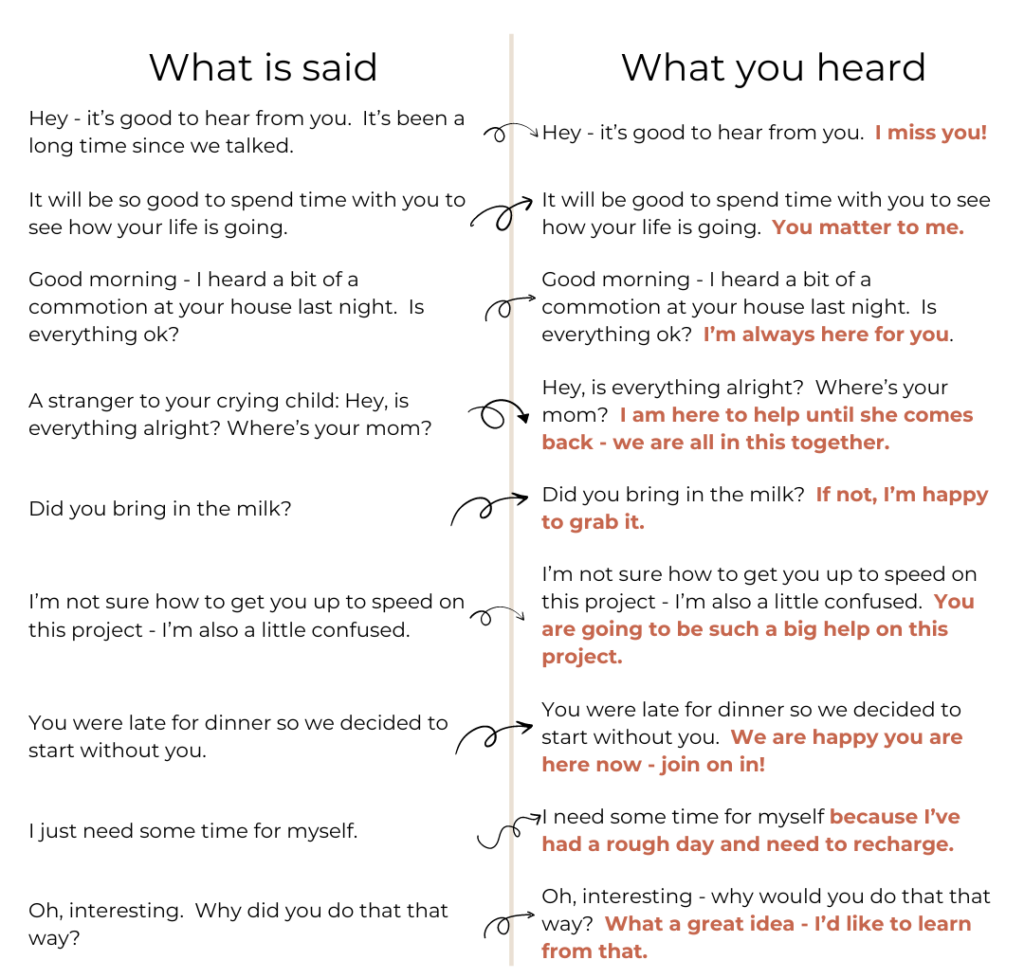

There are countless examples of this type of adding subtext to things that people say. Below are some examples. In both tables, the spoken words are the same, as shown on the lefthand side. In the first table, what is heard has been filtered through a person’s internal negative beliefs. The person doing the “hearing” or “interpreting” is imagining a negative spin on every message. Note that the added subtext is shown in bold.

Alternately, we can take those same messages, and say them to somebody else harboring fewer (or different) negative internal beliefs. Take a look at how completely different the resulting interpretation is. The added subtext is shown as bolded orange text.

It is even hard to see how the same messages could produce such different interpretations. We are doing this type of interpreting and adding subtext into many of our conversations. Consider how different your view of people and the world could be if you could conquer these messages.

Based on the tables shown above, it isn’t hard to imagine what the internal beliefs each of the listeners might be. Therefore, this can be a very powerful and informative way to identify the negative messages you believe about yourself and the world. Just devote the next day to noticing what type of additional messaging you are adding to other people’s words. Then examine if perhaps some of these additions reflect those beliefs about yourself. Once you have identified these beliefs, you can start to work on examining them and considering whether they are beliefs that are worth holding on to. Or maybe it’s time to let some of them transform.