Acknowledgement: It is not lost on me that while this essay is about questions, the essay is also filled with questions, that are intrinsically unanswerable by nature of being in this written communication. Rest assured that if I could hear the answers to these questions, I would be very open to doing so.

I think we would all agree, at least superficially, that questions and curiosity go hand-in-hand.

We ask questions for all sorts of reasons.

We ask factual questions – to get information (What’s for dinner? What is the weather forecast for today? What is the definition of collywobbles?).

We ask exploratory questions, where we are looking for opinion-based answers to something that we don’t already know. (How did you feel about the movie we just watched? What is your vision for the company for the next 5 years?)

And we can ask reflective questions – questions meant to reflect on big ideas and topics that we believe require deeper thought. (Have you considered how your attitude might be playing a large role in your inability to achieve your goals? or What did your experience in college teach you about the world?)

One might be tempted to think that all questions, by definition, are steeped in curiosity – wanting to really know more about or from the person of whom the question is being asked.

But is this really true?

I invite you to consider the following examples of questions that are intrinsically devoid of curiosity.

Throwaway Questions

We hear it many times each day – the all-too-common question: “How are you?” It’s been asked by millions of people countless times. But most of the time, it’s only a greeting posing as a question.

I perceive that it isn’t actually a question. Sure, sometimes you’ll get a half-hearted response – a brief, “I’m well” or “I’m fine” or “Not too bad.” That may or not be followed by a half-hearted, “How are you?”

But are most people really curious to hear the answer to that question? Do most people really want the real answer? Do people want to know what is really going on, how you really are? I wonder.

I’m certain that there are some truly curious people asking this question but you can usually tell the difference with their tone. Rather than saying, “Hi, how’s it going?” they are more likely to say “Hi, Jane, I’ve missed you. How are you? Tell me what’s been going on!”

Most of the time, though, in my experience, this question is generally not fueled by curiosity. Generally, the asker seems to be expecting the standard, canned response. They want you to respond with the formulaic “I’m fine, and you?” and move right along. It is very unlikely that they are open to hearing about your sick dog or your heartbreak about your having gained 5 pounds in the last week or your fear about your finances or your car breaking down. Most of the time, I think they are not wanting a rundown of what is plaguing your thoughts that morning. Furthermore, they probably don’t want to know that your 3rd-grade son just won the spelling bee or you are in line for a promotion at work. Most of the time, they aren’t actually curious to hear more, they are simply saying hello.

It’s a formality – a question with an expected canned response or no expected response. We have all been conditioned to follow this basic, yet hollow, script when greeting others.

In fact, most of us have become complacent and have long ago stopped being open to receiving what the other person is actually saying. The responses are predictable and boring, so we don’t really listen.

Some Ideas to Change It Up

- The next time someone asks you how you are, change the answer up – throw them a curveball. Maybe say something like “You know, thanks for asking. I am feeling angry at the moment, but I’m also grateful for this awesome mocha latte that I’m drinking.” Then pause and see how they respond.

- Try stirring things up a little bit by heading to a manned checkout lane at the grocery store next time and asking the clerk how they are doing. They will undoubtedly give you the canned response, but then say, “No, really, how are you today? How are you really feeling?” Then pause and see how they respond. I’ve done this before and some people will brighten and answer you truthfully while others will stay closed off.

- The next time you are greeting someone and you don’t really have the time or the interest to know how they are really doing, just say “Hello.” Don’t feel obligated to ask the throwaway question. If what you mean is “hello” then say “hello.”

Leading Questions

Another type of question that is used without curiosity is a leading question. These are questions that are intended to get a particular, or preferred response. These are questions that are seeking some type of approval or validation for the question asker. They are steeped in either unconscious or conscious control, and can be particularly maddening to the person being asked the question.

The key to identifying this type of question is to listen for the phrase “Wouldn’t you agree that…” before the question. This is an indicator that the asker is in some way looking for agreement with or validation of their opinion on a matter.

It does not convey true curiosity about another person’s opinions or thoughts. Furthermore, it leaves very little room for disagreement without some level of shame. Sure, the person to whom such a question is posed can disagree, but the implication straightaway is that they have a position to defend.

Maybe you have just watched a movie with a friend and the friend says, “Wouldn’t you agree that the undertones of that movie were extremely racist?” Perhaps you don’t agree. Perhaps you really enjoyed the movie and saw it as a great demonstration of the way the world is. However, now you are in a position to create conflict with your answer unless you answer with agreement. If you say yes, then you are not being honest with your friend. And if you say no, then they are poised for an argument because it sounds like they believe you are obviously in the wrong. A leading question begs for agreement and indicates a certain closed-mindedness in the mind of the questioner.

Imagine that this same question is asked in a different way – imagine that the question is asked “I thought that the movie had a racial undertone. What did you think?” This phrasing leaves more room for a difference of opinion and is more intrinsically open.

Leading questions are often asked across hierarchical levels by people in positions of explicit or implicit authority. Therefore, these types of questions are prevalent in the workplace. Let’s say you’ve been assigned a big project and are asked to come up with the project plan, which you will be presenting to the board. During the presentation, after you have presented the overall strategy for the project, one of the board members speaks up and says, “Wouldn’t you agree that spending three months on this project is too long?” Because the question is phrased this way, it puts you in a position to defend the timeline that you have clearly thought about and presented. It might seem apparent that you don’t agree with the speaker, but regardless you are now needing to defend your position.

In contrast, imagine that the board member phrases the question differently: “Why do you believe that we need to spend three months on this project?” If this question is asked and you are left ample time to truly answer the question, then the question is being asked with curiosity, rather than judgment.

Ideas to Change It Up

- Notice when you are beginning questions with “Wouldn’t you agree that….” When you find yourself doing this, remove that phrase from the question, and ask the question cleanly.

- Notice when others are beginning their questions to you with that phrase (“Wouldn’t you agree that…”) and ask them if they are truly open to hearing your honest response. Then give them space to answer your question.

Rhetorical Questions

Maybe you’ve been on the receiving end of questions that were never meant to be answered at all. Questions that are asked without truly expecting or even wanting a response. Similar to throwaway questions, rhetorical questions are asked without true curiosity about the answer. They are questions intended to make a point. And to go a step further, they are questions for which the asker assumes to already know the answer.

Have you ever been asked a question that sounded like a real question and you started to answer it but realized only too late that they didn’t actually want an answer?

We make so many assumptions in our worlds without stopping to get curious and actually consider that we might not know the answer.

We are so used to rhetorical questioning that when asked a question, we often misunderstand, thinking that the question is, in fact, an accusation. Even when the question is fueled by actual curiosity, we hear rhetoricality in it. Therefore, misunderstandings run rampant.

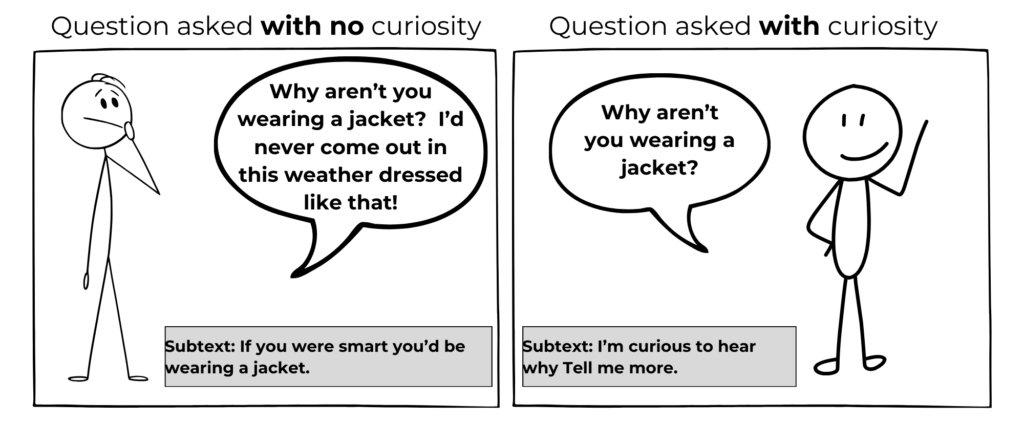

Consider the difference between “Why aren’t you wearing a coat?” (because I truly want to know) and “Why aren’t you wearing a coat?” (because I think you’re stupid). The difference is vast. The former is open for a response, while the latter is closed to responses.

Let’s consider a few other examples.

Personal Example

With Rhetorical Questioning

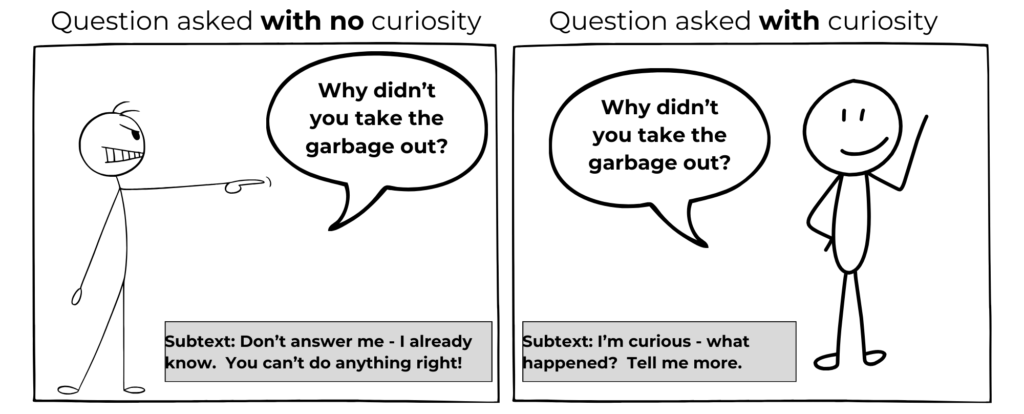

Let’s imagine that your spouse is angry that the garbage wasn’t taken out and you missed trash week. It had been your day to take the trash out to the curb and you had agreed to do so, but you had a crazy morning and you forgot to take it out. This conversation might go as follows:

“Did you forget the trash?!”

“Oh no, yes I forgot!”

“How could you have forgotten the trash? Now we are going to have to figure out where to put all of the extra garbage this week. What a pain! I can’t believe you forgot to take it out!”

What do you notice here? Do you notice that this entire last group of phrases actually started with a question? It started with the question, “How could you have forgotten the trash?” But do you think that the asker actually expected a response? Do you think that there was true curiosity behind that question? Do you think that this spouse truly wanted to know how their spouse could have forgotten the trash? It’s actually a fairly unanswerable question. I mean, is it being asked in the spirit of curiosity? I think not. Let’s reimagine this conversation now.

With Curious Questioning

“Did you forget the trash?!”

“Oh no, yes I forgot!”

“Why did you forget the trash?”

“I’m so sorry – I cut my finger this morning and had trouble finding the bandaids. That distracted me and the trash slipped my mind.”

“I’m sorry about your finger – is it ok?

“Yes, it’s ok now.”

“Well, that’s a bummer, and we will have to figure something out with the trash for this week but we can do that.”

The interaction with curious questioning goes far better than the one with rhetorical questioning.

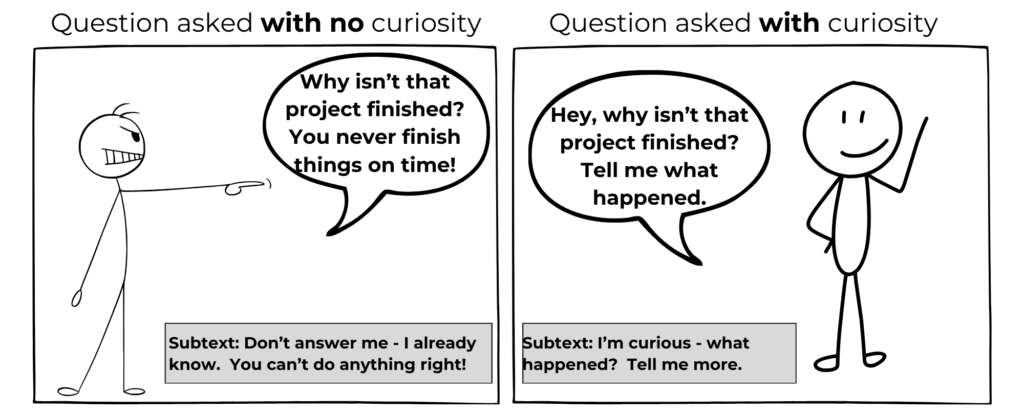

Business Examples

With Rhetorical Questioning

Say you are chatting with your boss and he says “Is that project finished?” With the all-too-brief pause that follows, you might begin to stutter out your answer, “Well, n-no” but your answer doesn’t matter because your boss isn’t listening. He is already on a tirade about how angry he is that the project wasn’t completed by last night.

Perhaps you had an actual answer for why the project wasn’t done – perhaps the client had emailed late in the day yesterday asking for an extension or offering additional details requiring a rework of the project that would by necessity change the deadline for the project.

However, once someone has asked a rhetorical question, their minds are closed off to true curiosity. They typically don’t want to know the actual answer – they have made up their minds about what they believe the answer to be, and they are moving forward believing that answer that they came up with in their own heads.

Often this exchange will end up with the question-asker dismissing any ensuing explanation as just an excuse. They might offer the all-too-typical, “I don’t want to hear all of your excuses! You said you’d have it done and it’s not done.” They might even turn and walk away from the conversation leaving you to wonder what happened.

At this point, the communication has completely broken down, leaving no room for solutions.

With Curious Questioning

This same interaction reframed with curious questioning might look something like this:

You are chatting with your boss and he asks about the project that was supposed to be done today, “Is that project finished?” You say, “Actually, I’m glad you asked – it’s not done because Sally Client Omega called yesterday and asked if we could rerun the analyses with a different set of assumptions. I told them we would complete the revisions by next week.”

Because the boss was willing to listen to the answer, and stayed open to hearing the actual answer, it was a healthy exchange. Even if the boss is disappointed that the project didn’t get completed on time, he conveys trust and openness to the real circumstances.

How Inner Voices Get in the Way of True Curiosity

We all have inner voices telling us what is true and what is not true. When we believe these inner voices without question and forget to stay open and curious, we can end up guilty of asking rhetorical questions.

Let’s say you became frustrated by something your friend or your employee or your partner has done. You don’t know why they chose to take that action, but you are upset. Your inner voice will fill in the details of why this has happened. If you choose to believe this inner voice without staying open and curious to discovering the real answer, you are choosing to believing your own jaded assumptions instead of asking the other person for clarity.

When the topic finally comes up with the other person, you have become so convinced that your inner voices are correct, you have begun believing the stories you have told yourself so completely, that you no longer see the value in listening to the other person. Even if this story diverges greatly from the truth, we often don’t question it. And because your brain has been believing this story that you invented for so long, it simply seems true now. You now believe that you don’t have to ask the question. You already know the answer.

Because you never did get curious and ask your partner, friend or employee about the situation, the belief you now have is entirely fabricated in your own head, but that usually won’t stop you from believing it.

This is fodder for all kinds of arguments and misunderstandings.

Examples of Inner Voices

“He doesn’t have to answer, I already know what the reason is. It goes without saying.”

“She won’t have a good reason for this – she failed and she knows it.”

“No excuse will make up for missing this deadline.”

Regardless of who it is, listening to people and actually being curious about what they have to say are both of the utmost importance in maintaining healthy communications and relationships.

This applies to everybody in your life.

This applies to people you perceive to be in a position of power over.

This applies to people you perceive to be in a position of power over you.

This applies to people you know well.

This applies to people you don’t know well.

This applies to people you’ve known for decades.

This applies to people you have just recently met.

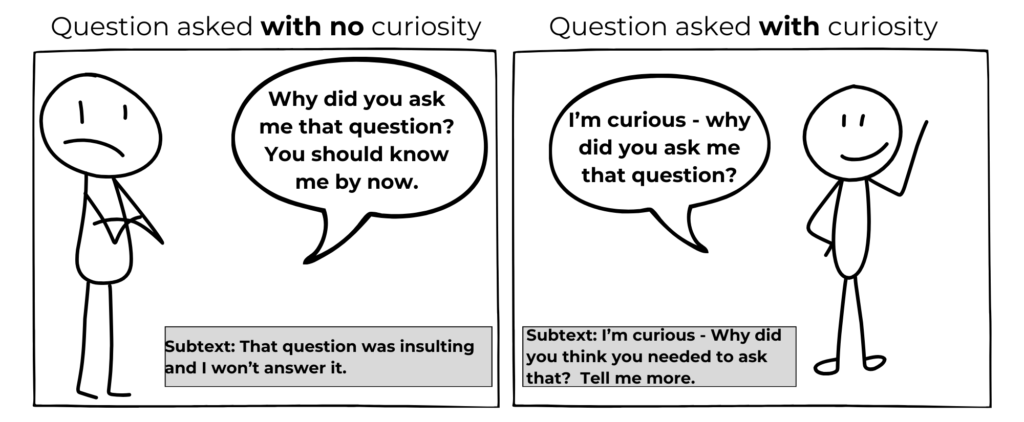

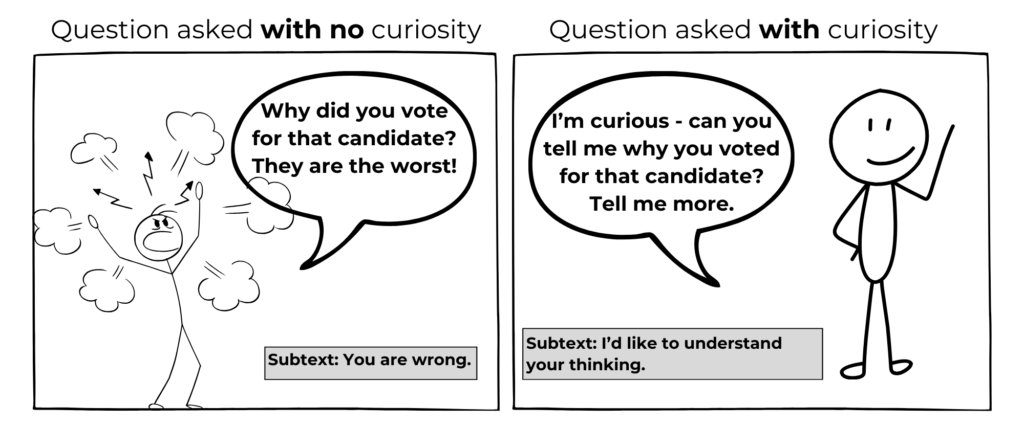

Examples of Rhetorical Questions

Let’s look at some examples of what this might look like in the real world. Notice that facial expressions and tone are extremely important in deciphering whether a person is asking a rhetorical question or a true question. I have added the subtext here to clarify the tone, as this is written communication and tone cannot be conveyed well in this context.

The primary way to identify a rhetorical question, though, is whether the asker gives you room to respond and then listens to your response.

Some Ideas to Change It Up

- Start noticing when you are asking rhetorical questions, identified by your not leaving space for or curiosity about an answer. When you find yourself doing this, stop yourself, get curious and flip the script by asking a question and then stopping to hear the answer.

- Start noticing when others are using rhetorical questions in their communications with you. When this happens, ask them if they are interested in hearing the answer.

- Start identifying the inner voices that you are listening to in the absence of true curiosity about other people’s actions. Instead of indulging in listening to these voices, try asking the person for clarity.

Self-Questioning

Now let’s questions that we ask ourselves. Do you ever ask your very own self rhetorical questions? Or maybe leading questions? Think about it for a minute.

As hard as it is to get curious about those around us, it is equally important (if not more important) to get curious about ourselves. I know that there is some old lore about people who talk to themselves being a bit off their rocker, but I strongly believe that everybody has some sort of internal dialogue with themselves, whether they like to admit it or not.

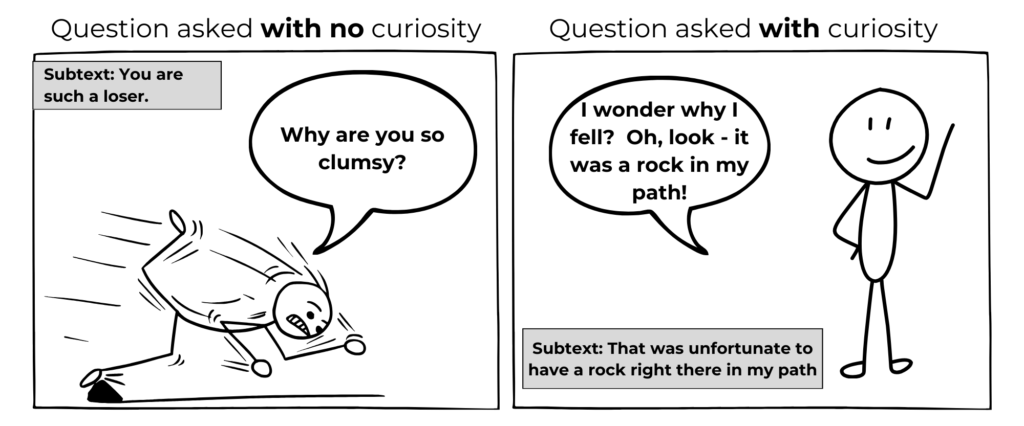

Think about walking down the street, tripping over an elevated part of the sidewalk, falling down and slamming down on the pavement, breaking your phone. (Yes, this has actually happened to me.) Might you ask yourself a question like – “How clumsy can you be?” “How stupid can you be?” Or some other related question?

These are rhetorical questions. Think about it – are you really open and curious to hearing a response? Maybe, but it’s doubtful. They are questions not meant to be answered. They are questions conveying judgment and condemnation.

But what if we switched it up and got curious instead?

What if you asked the more answerable question, “Why did I just fall?” and then stayed open for your own response. This question is filled with far less judgment and far more curiosity.

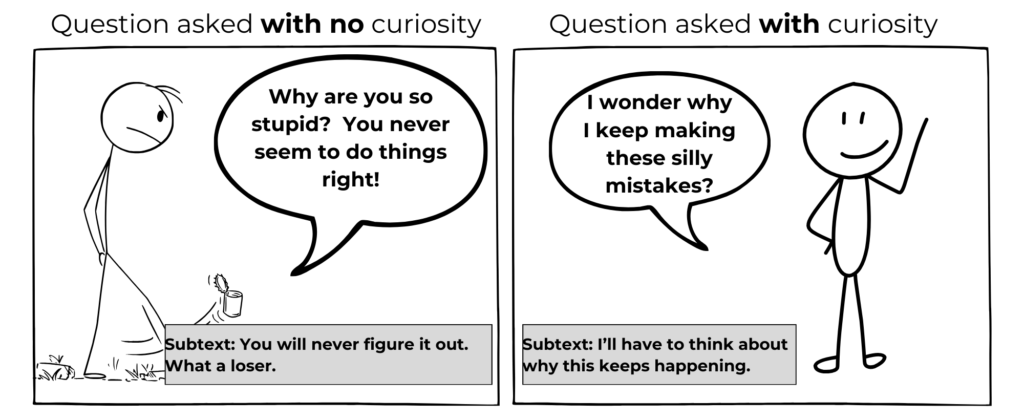

Or maybe you’ve just burned yourself on a hot stove and ask yourself “Why am I so stupid?”

Catch yourself in the act of asking that rhetorical question (otherwise known as beating yourself up). And then stop and consider – are you curious or are you judging? If you insist, you can still ask the question, but when you make curiosity your focus, the question might naturally change. With your new focus on curiosity, instead of asking the rhetorical and judgmental question, “Why am I so stupid?”, you might be more inclined to ask, “Why did that happen?” And then stay open and curious and listen for the answer. Maybe your answer to yourself will be that you’re too rushed. Maybe you will answer that you need buffer in your life. Maybe you’ll find out that you didn’t want to be cooking that dish to begin with and you were resentful and angry. Or maybe there is no particular reason. But be curious.

Tell Me More

In every situation, I encourage asking questions with a “tell me more” mentality. Imagine after every question you ask, you are adding on a “tell me more.” If that works, then it is probably a question worth asking. If it doesn’t work, consider whether you are truly curious to hear an answer. If so, try rephrasing the question so that a “tell me more” tagged on the end makes more sense.

Questions that don’t work

- “Wouldn’t you agree that the movie had racist undertones? Tell me more.” – Questions that are needing a specific answer don’t work well with “tell me more.”

- “Why would you plan three months for this insignificant little project? Tell me more.” – Questions that are thinly veiled accusations don’t work with the phrase “tell me more.”

- “Why are you so stupid? Tell me more.” – Questions that contain judgment don’t work with the phrase “tell me more.”

- “Why did you vote for that candidate? They are the worst. Tell me more.” – Questions followed by judgment don’t work with “tell me more.”

Questions that do work

- “Hi, how are you today? Tell me more.”

- “Did you think that movie had racist undertones? Tell me more.”

- “Why do you believe we need to spend three months on this project? Tell me more.”

- “Why didn’t you take the garbage out? Tell me more.”

- “Why aren’t you wearing a jacket? Tell me more.”

- “Why did you vote for that candidate? Tell me more.”

Ideas to Change It Up

- Notice the questions you are asking throughout your day. Consider whether you are asking questions because you are truly curious or if you are asking questions to condemn, judge or make a point.

- When you find yourself asking questions for which you truly do not expect an answer, either consider rephrasing them in a more honest way without the question.

- Or, on the other hand, or consider rephrasing the question so that you are actually open to a response. Rephrase the question so that you can add a “tell me more” onto the end of it and really mean it.

- And whatever you do, when you do ask a question, stay open and curious and listen to the answer.

Conclusion

In the end, questions serve as powerful tools to deepen our understanding and connection with one another. However, their true value lies in the curiosity that fuels them. Without genuine openness to receiving responses, our questions become hollow, their potential for insight lost.

Real curiosity invites richer exchanges, challenging our assumptions and broadening our perspectives. So, let us approach our questions – both questions we ask others and questions we ask ourselves – with the intent to listen and accept what we are being told. In doing so, we have the potential to transform our interactions into meaningful dialogues and allow curiosity to lead us to greater clarity and empathy.